Friday, December 18, 2009

Globe and Mail Arts Person of the Year: And The Runner-Up Is....

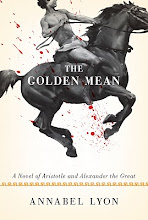

The Globe and Mail names me a runner-up for Arts Person of the Year (books)! Though a more deserving literary lioness would be Random House's editor extraordinaire Anne Collins, who edited both The Golden Mean and Linden MacIntyre's Giller-winning The Bishop's Man.

Other runners-up are Jason Reitman (film), Guy Laliberte (performance), and Christopher Plummer (film). The winner is hip-hop artist Drake. Congratulations!

To read John Barber's article, please click here.

Friday, December 11, 2009

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Hello, Edmonton!

To read Richard Helm's full article for the Edmonton Journal, please click here.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

Mieza

Mieza was supposedly cooler than Pella, the capital of Macedon, in the summer; it had shady walks and caves and (historians speculate) less to distract the teenaged prince than the big city.

Friday, December 4, 2009

The Artery Literary Saloon

I'm so pleased to be taking part in The Artery Literary Saloon this coming Thursday, December 10 at 7:00PM with Ted Bishop, Greg Hollingshead, Lynn Coady, and Marina Endicott. They're also promising something called the ALS Inaugural Book Smelling Contest. Come to the Artery, 9535 Jasper Avenue, Edmonton to learn more.

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Support the Food Bank / Win the Author!

From the BC Almanac website:

From the BC Almanac website:"Annabel Lyon's novel The Golden Mean has been showered with critical acclaim and awards. Now, you can have a chance at a Book Club meeting to remember with the author in attendance. Annabel Lyon will come to a Book Club meeting in the Lower Mainland to help discuss and dissect the book.

This one-of-a-kind prize package includes ten copies of the The Golden Mean.

The Donation Value: $800"

Join host Mark Forsythe on Friday, December 4th from noon to 3:00PM on CBC Radio One.

Monday, November 30, 2009

2009 Globe Books 100

The Golden Mean is on the 2009 Globe Books 100, the "best-reviewed, buzziest books of 2009". To see the full list, please click here.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

2009 Rogers Writers Trust Fiction Prize

"Annabel Lyon's Aristotle is the most fully-realized historical character in contemporary fiction. The Golden Mean engenders in the reader the same helpless sensitivity to the ferocious beauty of the world that is Aristotle’s disease. In this alarmingly confident and transporting debut novel, Lyon offers us that rarest of treats: a book about philosophy, about the power of ideas, that chortles and sings like an earthy romance."

Citation from the 2009 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize Jury:

Marina Endicott, Miriam Toews and R.M. Vaughan

The Golden Mean wins the Rogers Writers Trust Fiction Prize! For more details on all the winners and nominees, please click here.

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Word of the Day

The sarissa was invented by Philip of Macedon, Alexander's father. It was a pike, considerably longer than its predecessor, used in phalanx formations. The advantages were comparable to a boxer with an extra-long reach; the disadvantages included its considerable weight. A soldier needed both hands for the sarissa, entailing only a small shield hung from the neck.

Sarissa is also a girl's name, supposedly a derivative of Sarah, meaning "princess" or "lady" (see photos.)

Congratulations Kate!

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Scenes from a Giller

Michael Ondaatje (in response to my "You're Michael Ondaatje!"): "Yes, I am."

Rex Murphy : "Well, I know what you're doing here."

Clayton Ruby (on being told Victoria Glendinning had the envelope with the winner's name in her pocket): "I know some people who could get that. Want me to make a call?"

My mom: "There's Stuart McLean!"

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Giller Pics

Huffington Post

To read Marissa Bronfman's coverage of the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize for the Huffington Post, including interviews about the future of literature in a digital age, please click here.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Congratulations Linden!

Congratulations to Linden MacIntyre for winning the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize for The Bishop's Man. Linden and I share a wonderful editor in Anne Collins of Random House. Kudos!

Walrus Interview

"Depicting Aristotle’s tutelage of a young Alexander the Great, The Golden Mean is a gripping, thoughtful dramatization of one of the most intriguing relationships in ancient history."

To read my interview with Nav Purewal, please click here.

Indie Booksellers Pick The Golden Mean

To read Scott MacDonald's article in Quill and Quire, please click here.

Monday, November 9, 2009

Monty Python - Argument Clinic

A: The author of The Golden Mean thinks it's funny, that's what!

Saturday, November 7, 2009

Toronto Star Picks The Golden Mean!

The Toronto Star's Geoff Pevere picks The Golden Mean to win the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize! To read more, please click here.

The Globe and Mail does not pick The Golden Mean to win the 2009 Scotiabank Giller Prize! To read John Barber, Sandra Martin, and Alison Gzowski's takes, please click here.

Friday, November 6, 2009

Michael Enright Interview

To hear my interview with The Sunday Edition's Michael Enright, on CBC Radio One, please tune in on Sunday, November 8 at 9:11AM. For more information, please click here.

To hear a replay of the interview, please click here.

CTV Giller Coverage

For a full round-up of CTV's coverage of all things Giller (including a round table discussion with all nominees and a "what will you wear?" segment on Fashion Television), please click here.

Sunday, November 1, 2009

Toronto Star Interview

Thursday, October 29, 2009

IFOA

I'm so pleased to be taking part in the International Festival of Authors in Toronto. I have two readings to go: one at noon on Saturday with Ian Weir, Meaghan Strimas, and Nikos Papandreou; and then at 8:00PM is the Scotiabank Giller Prize shortlist reading with Anne Michaels, Linden MacIntyre, Kim Echlin, and Colin McAdam.

Tuesday, October 20, 2009

Hippocratic @#$%&*

Aristotle's father, Nicomachus, was physician to Amyntas, king of Macedon in Aristotle's youth, father of Philip, grandfather of Alexander the Great. Nicomachus practiced a generation or so after Hippocrates, one of the fathers of medicine, and I imagine he must have absorbed some of the radical teachings associated with him, such as the avoidance of superstition and the keeping of detailed case notes. I also imagine that Aristotle must have acquired a good bit of his father's medical knowledge; he certainly had a lifelong interest in biology, and his books reveal snippets of the expertise he must have acquired at his father's knee (see, for instance, his discussion of black bile in relation to melancholy in the Problems).

Here's a modern translation of the Hippocratic Oath (thanks, Wikipedia!):

I swear by Apollo the Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods, and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfil according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

To hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art–if they desire to learn it–without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken the oath according to medical law, but to no one else.

I will apply dietic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.

Whatever houses I may visit, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining free of all intentional injustice, of all mischief and in particular of sexual relations with both female and male persons, be they free or slaves.

What I may see or hear in the course of treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of men, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep myself holding such things shameful to be spoken about.

If I fulfill this oath and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being honored with fame among all men for all time to come; if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot.

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Globe and Mail Profile

Friday, October 16, 2009

CJAD Interview

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Governor General's Literary Awards

"Annabel Lyon’s The Golden Mean is a wise and subtle journey into the Court of Philip of Macedon, the mind of Aristotle and his complex relationship with his pupil, Alexander the Great. In this glorious balancing act of a book, Aristotle emerges as a man both brilliant and blind, immersed in life but terrified of living."

The Golden Mean has made the shortlist for the 2009 Governor General's Literary Awards! To see the full list, please click here.

Saturday, October 10, 2009

New Westminster News Leader Interview

To read the full interview with the New Westminster News Leader, please click here.

Friday, October 9, 2009

NXNW

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

"Giller jury picks tantalizingly varied list of finalists"

To read Geoff Pevere's full article for the Toronto Star, please click here.

Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Giller Shortlist!

The Golden Mean has made the Scotiabank Giller Prize shortlist! To see the full list of nominees, please click here.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

The Boy on the Cover

Alexander had an older half-brother named Arrhidaeus. The Roman historian Plutarch, who wrote a canonical early biography of Alexander, claims Arrhidaeus became an "idiot" following a childhood illness, or perhaps poisoning. In my novel, he's suffered brain damage as a result of meningitis (though the ancient Greeks, of course, had neither of those terms).

His affliction didn't seem to make him any less of a threat to Alexander, who freaked out (another term the Greeks probably didn't have) when their father arranged a politically convenient marriage for Arrhidaeus to the daughter of the satrap of Caria. Thinking Philip was positioning Arrhidaeus for the throne, Alexander sent an intermediary to the satrap, offering himself in his brother's stead. When Philip found out, he had the intermediary (a popular tragic actor named Thettalus) paraded through the streets in chains, and banished most of Alexander's closest friends. The offer of marriage, obviously, was withdrawn.

Arrhidaeus did eventually become king, after Alexander's death, and ruled with what we can only assume was enormous assistance from the general Antipater.

In the novel, I imagine Aristotle tutoring both princes: Alexander out of duty, Arrhidaeus out of scientific curiousity. In an early scene, the philosopher discovers Arrhidaeus loves horses and decides to teach him to ride. Once mounted, Aristotle wants the boy to sit up straight.

"'No, no,' a groom who's been watching them says. 'Now you hug him,' and leans forward with his arms around an imaginary mount. Arrhidaeus collapses eagerly onto the horse's back and hugs him hard."

Canadian Press Interview

It's the only book to make both races this year, and the competition is stiff: The Giller long list, which will be narrowed to a short list on Tuesday, includes Margaret Atwood, and the Writers' Trust list of finalists includes Alice Munro."

To read the full interview with Victoria Ahearn for the Canadian Press, please click here.

Wednesday, September 30, 2009

Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize

The Golden Mean has been shortlisted for the 2009 Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction Prize! To see the full shortlist, please click here.

Tuesday, September 29, 2009

Royal Tombs

Aegeae is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The UNESCO website asserts, in part, that "the site is of outstanding universal value representing an exceptional testimony to a significant development in European civilization, at the transition from classical city-state to the imperial structure of the Hellenistic and Roman periods". To see the website for the museum at Vergina, click here.

This short video clip offers a brief look at the remains of Aegeae and some of the artifacts discovered there, including the Philip's larnax and gold wreath.

Monday, September 28, 2009

Word of the Day

The name "Kandahar" is a corruption of "Alexander" ("Iskander" in ancient Persian). Alexander the Great founded the Afghan city in 330BCE.

I found this photo on flickr.com. It was taken just outside Kandahar, Saskatchewan.

Friday, September 25, 2009

Word on the Street

I'm very pleased to be taking part in Word on the Street this coming Sunday (September 27) at Library Square in Vancouver. I'll be in the Author's Tent at 3:00PM for a reading from The Golden Mean and an on-stage interview with Steven Galloway (The Cellist of Sarajevo, Ascension, Finnie Walsh). It's going to be a beautiful sunny day; come on down and say hi!

Monday, September 21, 2009

Sunday, September 20, 2009

Montreal Gazette Review

"Whether posing the eternally relevant question of what it means to live a virtuous life, detailing the gory details of an ancient battle scene or probing the relationship between master and student, Lyon authoritatively evokes a fabled time and place in the urbane and dry voice of the man judged the smartest of his age."

To read Elaine Kalman Naves's full review for the Montreal Gazette, please click here.

Friday, September 18, 2009

Aristotle on Religion

"[T]here is, in Aristotle's view, no divine providence, which is so important an aspect of the Judeo-Christian view of the world. His god does not look out for, care about, and provide for man. He did not create the universe, for it is eternal, and he is utterly indifferent to it. It is true that he causes its motion, but only as a beautiful picture might cause a man to purchase it. God is the object of desire for the lesser intelligences, but he is unconscious of their admiration and would be indifferent to them if he were aware of them.

"In Aristotle's view god is a metaphysical necessity--the system requires an unmoved mover, a completely actual and fully realized form, but he is not an object of worship. Aristotle did not experience a Christian's love of a heavenly father, nor the Orphic's need for union with a mysterious, infinite power. Aristotle's god is transcendent and remote, and his attitude toward this god, at least as revealed in the Metaphysics and other works of his maturity, was emotionally neutral."

from W.T. Jones, A History of Western Philosophy, volume I: The Classical Mind (2nd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970, pp.231-2)

Monday, September 14, 2009

The Bacchae

ca. 27 B.C.–14 A.D.; Augustan

Pentelic marble; H. 56 5/16 in. (143.03 cm)

Euripides, the youngest of the three great Greek tragedians (after Sophocles and Aeschylus) spent the last year of his life in Macedon as a guest of the king, Archelaus, dying there in 408 BCE. His play The Bacchae took first prize at the festival in Athens after his death.

Euripides was known for his use of strong, complex female characters. In the Poetics, Aristotle writes that Sophocles portrayed people as they ought to be but Euripides portrayed them as they were.

Performances of The Bacchae bookend The Golden Mean. It's a darkly funny, violent play that features the god Dionysus descending in human form to humiliate a priggish king for his disrespect. The god persuades the king to dress as a woman and sneak in to observe his mother and her friends engaged in Bacchic rites. The women uncover the deception but in their frenzy fail to recognize their king and rip him to pieces. His own mother carries his head home, believing she's killed a mountain lion, and only slowly recovers to realize she's dismembered her own son.

The play was a court favourite in Pella, and I open the novel with a performance of it for the royal family. Aristotle befriends the play's director, a fictional character named Carolus, who encourages the young Alexander's interest in the theatre. The novel ends (neatly, I hope!) with Philip's murder at a performance of The Bacchae , part of celebrations for his daughter's wedding.

The image above is of a dancing Maenad or Bacchante, a female follower of Dionysus (Bacchus). Notice her thyrsus, a long stick wrapped with ivy symbolizing her fidelity to the god, and her gorgeously flowing robes.

Thursday, September 10, 2009

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

2009 Whistler Readers and Writers Festival

Monday, September 7, 2009

Calgary Reading

Whistler Writers Group Weblog

"It was exhilarating to be transported so effortlessly to a long ago place and time, peopled by vaguely familiar characters – Aristotle, Plato, Cleopatra, Alexander the Great – who now skitter about vividly in my mind’s eye."

To read the full post, click here. To see the line-up for the 2009 Whistler Readers and Writers Festival, click here.

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Creating Character: Pythias

A typical woman of Pythias' time and status would have lived an exceedingly circumscribed life. She would have received no formal education, and would probably have married in her early teens. She would not have had possessions; she would not have left the house very often; she would probably have been illiterate; she would have had a good chance of dying in childbirth.

Not the happiest bundle of probabilities. As a 21st century novelist--as a 21st century woman--I wanted more for her. I thought about different ways of introducing a strong female character into the novel, but they were all cliches of one sort or another. Aristotle's wife really wrote his books! Aristotle was secretly engaged in a taboo love affair! Female academic, 2400 years later, uncovers some shocking secret about the great man!

None of these appealed to me. Partly because they've been done, sometimes wonderfully well (think of A.S. Byatt's Possession); partly because they felt dishonest. I wanted to look history in the eye and reckon with the woman as she probably was, not as I anachronistically wanted her to be. In The Golden Mean, Pythias is neither bright nor stupid, beautiful nor ugly. She wants a child but doesn't really like sex. She's literate (I made this a pet project of her husband's), but doesn't make much use of this gift. She's quiet. She has kindness in her and a bit of unexpected steel, too. She likes nice clothes. She dies too soon, in fear, and leaves behind a frightened, lonely little daughter.

Aristotle's own writings clearly rate women's intelligence beneath men's, and approves of their status as second-class citizens. I don't like the fact that he owned slaves, either; I hate it. But I couldn't bring myself to blink these things away. Fiction requires its own kind of fidelity. "Tell the truth, but tell it slant," Emily Dickinson famously wrote. For me, the operative word here is truth. Fiction is not the place for self-indulgent wish-fulfillment, even when you've got the moral high ground and the best of intentions. With Pythias, I had to choose between feeling good and feeling true. I chose true.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Westender Interview

To read Steven Schelling's full article for the Westender, please click here.

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Unmentionables

velvety I used this to describe a baby's scalp before discovering that velvet was a Medieval fabric, unknown to the ancients.

rubbery To describe a person's face. Oops.

stirrups Invented by the Romans. The Greeks had saddles; the Macedonians, great horsemen, liked to ride bareback.

Caeserian This operation actually was performed by the ancient Greeks (with one shudders to guess what success), but the term was obviously of Roman origin. I had to get the incision in the right direction, too; initially I had Aristotle's father make the cut along the bikini line, as surgeons would today; but until quite recently, surgeons cut from the navel downwards, leaving a vertical rather than a horizontal scar.

And some of the words I got away with:

silk The famous silk roads, the great trading routes between Europe and Asia, were opened up by Alexander, so silk would have been all but unknown before his great campaigns. I had to change all Pythias's dresses from silk to historically accurate linen. I did allow myself to keep one metaphorical use ("the truth slipped like silk") because I just couldn't come up with a word I liked better.

tar The ancients had pine tar, particularly useful for sealing ships.

beer The Macedonians brewed barley beer, something like Medieval mead. Because the weather in mountainous Macedonia tended to be cool and rainy in the winters, grapes didn't thrive as well as in the warmer, sunnier south, and wine had to be imported.

fuck The Greeks looked on the Macedonians as vulgar barbarians, wealthy but crude, who had to import what culture they possessed. Looking for a way to distinguish in English between Greek and the Macedonian dialect, I struck on an analogous use of British and North American English. My Athenians would speak like Brits, my Macedonians like North Americans. "Do they have to curse like rappers?" an acquaintance (born in England) asked me plaintively after reading a draft. Exactly!

The 26-volume Oxford English Dictionary was an invaluable resource when anachronism became a worry. It not only provides definitions, but cites the first known use of your word, a huge bonus for the historical novelist. If anyone's wondering what to get me for Christmas....

Tuesday, August 25, 2009

Sunday, August 23, 2009

Winnipeg Free Press Review

To read Ezra Glinter's full review for the Winnipeg Free Press, click here.

Thursday, August 20, 2009

Georgia Straight Profile

To read Alexander Varty's profile in the Georgia Straight, please click here:

With The Golden Mean, Annabel Lyon revives ancient ethics | Vancouver, Canada | Straight.com

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Monday, August 17, 2009

Aquamanile: Phyllis Riding Aristotle

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Vancouver Sun Review

To read Joe Wiebe's lovely profile and review for the Vancouver Sun, please click here: The philosopher and the warrior

Friday, August 14, 2009

Reviews

Read Cynthia MacDonald's full review of The Golden Mean for the Globe and Mail here.

“...an audacious attempt to create a flesh and blood Aristotle, with intimate glances into his psyche...”

Read Philip Marchand's full review for the National Post here.

“Lyon must be applauded for a daring and challenging approach to fiction.”

Read Candace Fertile's full review for the Edmonton Journal here.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Oh, Those Romans (Film and TV)

One problem that came up again and again was diction: for some reason, all my characters kept trying to talk like they were British. I realized this went back to Robert Graves . I first watched the great 1976 BBC adaptation of his novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God when I was a child. Despite the English accents, the dialogue is fresh and spiky without sounding anachronistic (see clip below).

I had hopes that the recent HBO series Rome would have an even more contemporary feel. Indeed, despite (again!) the English accents, the characters felt immediate and recognizable, people you could talk to rather than just listen to.

Finally, for a bit of cinematic ancient Greece, find Pier Paolo Pasolini's astonishing 1967 movie Oedipus Rex. Pasolini has claimed that the film was autobiographical. An intense, beautiful, strange journey through a landscape that's both dream-like and utterly credible.

Here's a clip of one of my favourite I, Claudius characters, the empress Livia, instructing her gladiators:

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

Martha the Great

I first read Martha Nussbaum as an undergraduate philosophy student at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, BC. The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy examines the ethical thought of Plato and Aristotle, but also Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, as manifested in their tragic dramas. When I read this book, a lot of vague and unsettled ideas I'd been struggling toward fell into place with one of those profoundly satisfying clicks you hope to experience once or twice in your intellectual life. I realized my interests in fiction and philosophy were not mutually exclusive. Not only could they co-exist, they might in fact be different facets of the same interest, two itches that could be scratched with the same finger.

Love's Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature continues her project of mining literary works for ethical and philosophical insights. It includes essays on Aristotle, Plato, Henry James, Charles Dickens, and Samuel Beckett. She's also written books on education, religion, economics, and law.

Martha Nussbaum is the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Sunday, August 9, 2009

Today's the Day!

Saturday, August 8, 2009

The Ancient City of Pella

Pella was a wealthy, modern city for its time. In addition to being a political centre, Pella was a significant commercial hub and featured an enormous marketplace surrounded by arcades and workshops. Here's a look at the archeological remains:

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

And Now for Something Completely Different

Monday, August 3, 2009

Creating Character: Philip

This, to me, is elegant menswear. Philip's helmet was buried with him in his tomb, in Vergina, and can be seen today in the museum there. Philip inherited a kingdom in perilous disarray; by the end of his life, Macedon ruled all of Greece, and Philip's troops were preparing to invade Persia. Were he not subsequently overshadowed by his more famous son, Philip would be remembered today as one of the most brilliant rulers of the ancient world. He was a fun character to create, a likeable rogue: a fierce soldier, canny politician, drinker, womanizer, and surprisingly pragmatic diplomat.

His conflict with Alexander sprang, I think, from the fundamental difference in their characters: Philip wanted to conquer the known world, but Alexander wanted to conquer the unknown world. For all their similarities, he lacked his son's compulsive curiousity. The Oedipal conflict is also vivid in Philip and Alexander's relationship. Freud read Shakespeare; Shakespeare read Plutarch; and Plutarch, one of Alexander's earliest biographers, would have known his Sophocles.

Philip was stabbed to death at his daughter's wedding by one of his bodyguard, a man named Pausanias. Historians have speculated the assassin was hired by Alexander, impatient to assume the throne; or his mother, Olympias, jealous of Philip's recent marriage to a much younger wife; or both of them together. Conveniently, Pausanias is supposed to have tripped as he ran across a vineyard toward his getaway horse, and was caught and torn to pieces before he could be questioned.

Thursday, July 30, 2009

Historical Fiction Faves

As James Wood wrote in a recent New Yorker review, "Sometimes, the soft literary citizens of liberal democracy long for prohibition. Coming up with anything to write about can be difficult when you are allowed to write about anything. A day in which the most arduous choice has been between "grande" and "tall" does not conduce to literary strenuousness."

The historical fiction I enjoy tends to subvert or ignore the tropes of the genre. Here are three novels about the ancient world that subvert, surprise, challenge, and please.

David Malouf's An Imaginary Life (1978). The Roman poet Ovid is exiled to a barbarian village at the edge of the Black Sea, where he ends up caring for a feral child. Most historical fiction tries to impress the reader with the sophistication of the period it recreates (for some reason my mind jumps here to Gwyneth Paltrow's toothbrush thingy in Shakespeare in Love). Malouf, in contrast, portrays the absolute fear and dread of the 'civilized' mind (represented by Ovid) in the face of the truly primitive. The author powerfully conveys the sheer otherness of the ancient world.

Grant Buday's Fireflies (2008). A prose retelling of the Iliad from Odysseus' point of view. The great strength of Buday's novel isn't in any formal innovation or revisionism. Rather, it's the crispness and humour and beauty of the prose that make this book worth seeking out.

Mary Renault's Fire From Heaven (1969). The first twenty years of Alexander the Great's life, including his time with Aristotle, from the boy's own point of view. This novel is the first of a trilogy about the life of Alexander. I avoided reading this one for a long time because it dealt with many of the events I was writing about, and I didn't want to have my conception of events influenced by another fiction writer. When I finally finished my own novel and allowed myself to read Renault, I was relieved I hadn't read her sooner, because I would have been completely psyched out: the writing is excellent, the research immaculate, the characters psychologically profound. I particularly appreciated her no-nonsense portrayal of Alexander's bisexuality. A lesser author would have made this the focus of the novel, but Renault is cool enough not to let the hot stuff derail her larger narrative.

If you're wondering when I'm going to get around to Robert Graves, the answer is in a future post about TV and film, since I was introduced to his work through the great 1976 BBC adaptation of his novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God. Stay tuned!

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

Monday, July 27, 2009

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Melismos

The music is an Invocation to the Muse. Translation: 'Sing for me, dear Muse, begin my tuneful strain; a breeze blow from your groves to stir my listless brain' and 'Skillful Calliope, leader of the delightful Muses, and you, skillful priest of our rites, son of Leto, Healer-god (paean) of Delos, be at my side' (J. G. Landels).

Hang on for a haunting ending on the frame drum.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Creating Character: Alexander

Alexander The Great

Originally uploaded by Philippe C.

I knew I wanted the kid to be annoying. There's a reverent literary tradition around Alexander, beginning with his first biographers (Arrian, Plutarch), through the so-called Alexander Romances of Medieval times (where he often had superpowers), right up to the present (most recently with Oliver Stone's 2004 biopic Alexander, featuring Irish heartthrob Colin Farrell).

But years as a teacher have taught me that teenagers with brains and talent are often the most arrogant, insecure, and impossible students of all. I wanted to create a character who would both defy expectations and be immediately recognizable to anyone who's ever had to deal with an exceptionally bright, difficult teenager. I pictured the young Alexander as an annoying narcissist who needed to be taken down a few notches. Just the job for my fictional Aristotle, whose brilliance I much preferred (in the beginning, anyway) to Alexander's brawn.

But I struggled. Early readers told me they believed Alexander as an annoying teenager but couldn't see the seeds of the man who would conquer the world. The more I thought about him, the more he bothered me. I knew he needed to be more than just a smart-aleck, but I still couldn't buy into the tradition of the sexy, hotheaded military genius.

The penny finally dropped when I read an article in the September 29, 2008 New Yorker about an Iraq war veteran suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (William Finnegan's "The Last Tour"). I was struck by the symptoms Finnegan described--headaches, nightmares, alcoholism, loss of touch with reality, and most of all the paradoxical desire to be at home when you're at war and at war when you're home. These symptoms fit the later Alexander (an alcoholic given to fits of blinding violence immediately followed by crippling depressions, who left home at 19 and never returned).

The more I thought about the boyhood that must have preceded this tormented life, the more I wondered if the trauma might have begun very early indeed. His parents by all accounts hated each other. His father took numerous wives and produced half-siblings often enough to keep the young prince's expectations about his future off-balance. His mother was suspected of witchcraft. Alexander was trained as a child soldier, leading troops into battle when he was only 16.

Child soldiers exist today, and we know what damage and trauma they suffer (when we allow ourselves to think about them at all). An ancient child would have suffered no less. Once I understood that, I understood how to proceed with the character I now cared and feared for as much as anyone in the novel.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Aristotle's birthplace

The Athenians never considered Aristotle one of their own. Though he spent the last twelve years of his life living and teaching in Athens, he was forced to leave the city after Alexander's death, when Athenian sentiment turned against anyone associated with Macedon. Aristotle is supposed to have said he didn't want "the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy", a reference to Socrates' execution.

Here's a 30-second clip of the ruins of Stageira:

Tuesday, April 7, 2009

And Now, Some Recipes

He found a drink made of a mixture of grape wine, barley beer and honey mead. (In both the Iliad and the Odyssey, Homer describes a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey, and goat cheese). Small jars contained fatty acids and lipids associated with sheep or goat fat; phenanthrene and cresol, suggesting the meat was barbecued before it was cut from the bone; gluconic, tartaric, and oleic/elaidic acids implying the presence of honey, wine and olive oil respectively (perhaps a marinade?); and a high-protein pulse, likely lentils. Traces of herbs and spices completed the dish.

Despite its far-reaching spider web of trade routes (particularly in the wake of Alexander's great Eastern campaigns), the ancient world was made up largely of locavores. (We moderns think we're so trendy!) A typical Macedonian diet in Aristotle's time would have featured a lot of bread and fish, and seasonal fruits and vegetables. (Both Alexander and his father, Philip, were supposed to have had a passion for apples).

Meat was a luxury unless you were extremely wealthy. Goat and mutton were most common; chicken, duck, goose, and rabbit were also available; beef was rarely eaten. Staple proteins were beans, eggs, cheese, yoghurt, and nuts. Wine was brewed far stronger than we know it today and was usually served with water, as we'd serve scotch. Barley beer was popular in Macedon, less so in warmer, sunnier southern Greece, where grapes were more plentiful.

Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon's Vancouver-centric The 100-Mile Diet: A Year of Local Eating was surprisingly helpful when I tried to picture an ancient kitchen. It made me think about all the foods I took for granted that Aristotle would never have heard of (black tea, coffee, mangoes, sugar, pepper, salmon, chocolate, etc.). It also made me think hard about food storage and seasonal availability; at one point I caught myself giving my characters a meal of roast lamb in autumn--whoops. In the final draft, they get goat.

Historical novelists like to describe food. It's a double urge, I think: to surprise the reader with the sophistication of the era they're describing, and to make the period instantly accessible. How hard is it to imagine sitting down to a plate of feta and walnuts, or a nice, spicy lamb-lentil stew and a beer?

A couple of websites featuring approximations of ancient Greek recipes are ancientgreekfood.net and greek-recipe.com.

Saturday, April 4, 2009

Ten Uses for a Philosophy Degree

2. Go to graduate school. You're never going to get a real job.

3. Go to law school. Oh, thank god, thank god, she's come to her senses. She says those logic courses helped her with the LSAT and having studied ethics might be a real advantage. No, of course I didn't tell her that. You want to put her off before she's even started?

4. Become a nihilist. You dropped out of law school? After one year? What do you mean, you're depressed? We're all depressed! But they'll take you back, right, when you come to your senses? And put that black t-shirt in the laundry, my god, don't you own any other clothes? Don't you want a pension and dental? What is the matter with you?

5. Laugh extra hard at that Monty Python sketch about the all-Bruce philosophy department at the University of Walamaloo (Australia, Australia, Australia, we love you!).

6. Fan yourself with it while imagining you're Lasthenea of Mantinea or Axiothea of Phlius, the only women known to have attended Plato's Academy.

7. Get an MFA in Creative Writing. So, graduate school after all. Which is more useless, do you think, philosophy or creative writing? Hmmm?

8. Read your old textbooks when you feel stressed. Seriously, you do that? Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics? Seriously?

9. Get a job in spite of it. Teaching writing? Do you get a pension and dental with that?

10. Write a novel about Aristotle. I began The Golden Mean in late-September 2001. Like many other privileged North Americans in the arts, I was questioning the relevance of my work in the aftermath of the attacks in New York and Washington. I struggled to read and write fiction, but found some solace in Aristotle. The things he thought about 2300 years ago--what makes a good government? what's a tragedy? what does it mean to lead a good life?--were the things everyone was suddenly thinking and talking about. For me, his words were serious, intelligent, contemporary, alive.

One day I read the thumbnail bio in the front of my copy of his Ethics and found myself wondering--just wondering, really. What would he have made of contemporary political polarities? What did he eat for breakfast? Did he like teaching? Why the particular interest in marine biology? How did he meet his wife?

Finally, I realized the only way I would ever find my way back to the abiding worth of fiction was through this most challenging, engaging, and relevant of subjects.

Friday, April 3, 2009

Aristotle's Thought, Sort Of

(This is the first of three clips from the same lecture, all available on Youtube.)

Thursday, April 2, 2009

All the Life You Can Fit on a Postage Stamp

Vienna, Museum of Art History, Collection of Classical Antiquities. Head of Aristotle.

Originally uploaded by sssn09

From the ocean of historical knowledge, what's known for sure about Aristotle's life would fill a thimble. Good news for this fiction writer (though some historical novelists seem to thrive on a wealth of detail - I'm thinking of Colm Toibin's The Master, inspired in no small part by Leon Edel's five-volume life of Henry James).

The bare bones are these: Aristotle was born in 384BCE in Stageira, Thrace. His father, Nicomachus, was physician to the king of Macedonia, and one can assume both from Greek custom and from Aristotle's subsequent writings that he absorbed a lot of knowledge of his father's trade. It's likely that at this time Aristotle met Philip, the future king of Macedon, then a teenager like himself. From Aristotle's will we know he had a sister and brother, Arimneste and Arimnestus. Arimneste had a son, Nicanor; Arimnestus died childless.

At seventeen, Aristotle went to Athens to study at Plato's Academy. He remained there for almost twenty years, first as a student and later as a teacher, leaving only after Plato's death.

He then spent some years in Asia Minor under the patronage of Hermias of Atarneus. In 343 or 342BCE Aristotle went to Pella, the Macedonian capital, to tutor Philip's son, Alexander. He remained in and around Pella for about seven years, until Philip's murder and Alexander's ascent to the Macedonian throne.

Aristotle then returned to Athens to head the Lyceum, a rival school to the Academy. He remained there for another twelve years or so, until Alexander's death, when Athenian sentiment turned against anyone with Macedonian connections. Aristotle then left Athens for Chalcis, which offered the protection of a Macedonian garrison. He died there a few months later.

As for Aristotle's love life, we know (again from his will) that he had a wife, Pythias, who bore him a daughter, also named Pythias. He also had a companion named Herpyllis, who bore him a son named for his father, Nicomachus. In his will, Aristotle makes affectionate provision both for Herpyllis and for the marriage of his daughter to his sister's son, Nicanor. He also provides for his many slaves. He asks that his own bones be laid with those of his dead wife, "in accordance with her own wishes".

So what's a fiction writer to make of all this? Twenty years at the Academy; another twelve at the Lyceum. Years of genius, all of them; but an explosive life of the mind can look suspiciously like a man sitting quietly in a comfortable chair, staring at his lap. Not promising material for a novel (unless you're Colm Toibin!), so I chose to focus on the seven tumultuous years Aristotle spent at the Macedonian court.

The image above is a Roman copy, mid-1st century, of a Greek original ca. 320BCE.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Welcome!

When I began writing this novel, in 2001, I didn't imagine it would take eight years to finish. Though I guess I should have known: my first book, Oxygen, took six years; my second book, The Best Thing for You, took five; and my children's book, All-Season Edie, took a ridiculous twelve years from start to finish. (Admittedly with some long periods of inactivity in there!) But I thought for sure this one would go faster. Because it was a novel, a form new to me, I planned a meticulous outline, scene by scene, and stuck to it like a terrier. Because I wrote most of the book while pregnant (twice) and/or caring for small children, I set myself targets: 200 words while they nap! Go! And slowly, slowly, paragraph by paragraph, scene by scene, the novel accreted. My embryonic first draft of thirty pages or so eventually became two hundred plus, and then the process of revision began. Ten or so drafts later (you think I'm kidding?), my editor gently suggested I let the book go. It's now set to hit the world on August 25, 2009. I hope this blog will spark interest in Aristotle and his relationship with the young Alexander the Great, and perhaps lead to some discussion of his relevance to the modern world. Welcome!